Mammies and Mothers: The Challenging of Black Female Stereotypes in Bill Traylor’s Lexicon

The work of Bill Traylor details life as an African American living in 1930’s Alabama. By providing an analysis of a small sample of Bill Traylor’s more than one thousand surviving works detailing black womanhood in different facets, contemporary readers of his work gain an understanding of the nuanced versions of black womanhood that differ from the images of black women in popular imagination.

Bill Traylor was born into slavery in 1853, near Dallas County, Alabama. At the age of twelve, he and his family were emancipated and began working as tenant farmers on a neighboring plantation. After his third wife left him widowed, Traylor moved to Montgomery, where he lived from around 1927 until his death in 1949. During his life he fathered fifteen children, had transitioned from enslavement to emancipation, had briefly lived in Detroit, Philadelphia, and Washington D.C. with his grown children, and had returned to Alabama and started an artistic journey where he created more that one thousand works. [1] As a black folk artist, Bill Traylor had a keen insight into what it meant to depict black girls and women in a nuanced way that both white and black folklorists and ethnographers were unable to capture, a deviation from the imagery and stereotypes that proliferated not just art and literature, but historical events. Traylor’s visual lexicon depicted black women in 1930’s Montgomery in a way that emphasized their agency and candor, which differs from their depiction in the memoirs collected for the Alabama branch of the Federal Writers Project of the 1930’s. These records were meant to “set beside the work of formal historians, social scientists, and novelists” and to enhance the work of social psychologists and cultural anthropologists. Emphasis on the slaves telling stories in their own words “in spite of obvious limitations of the fallibility of the informants and interviewers, unskilled techniques, and insufficient controls and techniques.” B. A. Botkin, chief editor of the Writers’ Unit for the Library of Congress Project, called this a “colorful” source of knowledge. While their stories are transcribed by the writers, their inner worlds are ignored, and the context of their lived experiences is divorced from the stories that are recorded. In stark contrast, Traylor put tremendous thought into his compositions and overall artistry, so his title as folk artist or self-taught artist is reductive to the quality of work he was able to produce through his “allegorical and symbolic visual lexicon.”[2]

Mother with Child

An analysis of Mother with Child gives insight on the perspective Traylor had regarding black motherhood. The drawing shows a black woman facing away from her daughter, while carrying a purse. This type of matriarchal representation depicted black motherhood outside of the context of a labored setting. On the back of the drawing, Traylor writes “child begs mother not to leave.”[3] Traylor would have multiple examples of motherhood to draw from, including his relationship with his own mother Sally, and the relationships that his children had with their respective mothers. The mother in this work, dressed in modern fashion and shown with her child, interrogates the imagery of black mothers providing maternal labor to white children during both slavery and the early 20th century. Many black women continued to work as nannies and domestic workers after emancipation, and the image of the hyperbolized mammy came into popular use during the Jim Crow era. This stereotype existed as a reminder of the specific form of labor that black women provided, a labor which existed outside of their own family structures. One of the informants from the Federal Writers Project, Matilda Pugh Daniel, explained how her own mother spent most of her time catering to the needs of the slaveowner’s children, without time to properly care for her own children, even when they became sick.[4] The raising and caring of black children was secondary to the work of caring for white children, and even after slavery, black motherhood was occasionally demonized. In the case of stepmother Teaner Autrey, the Tuscaloosa News reported that she murdered her two-year-old stepdaughter by pushing her into a bucket of scalding mop water. She was later granted clemency from the governor of Alabama, which saved her from the death penalty. [5] Events that highlight the pathology of black motherhood, contrast with Traylor’s depiction because although the mother is not especially nurturing and her gaze is in the opposite direction of her child, the desire her child expresses for her mother not to leave, presumably to take care of business outside of the domestic sphere, could be read as a close and loving bond between the two. It is a very universal sentiment expressed by young children in relation to their first caregivers and a sentiment that Traylor illustrates in spite of the labored and pathologized stereotypes of black women.

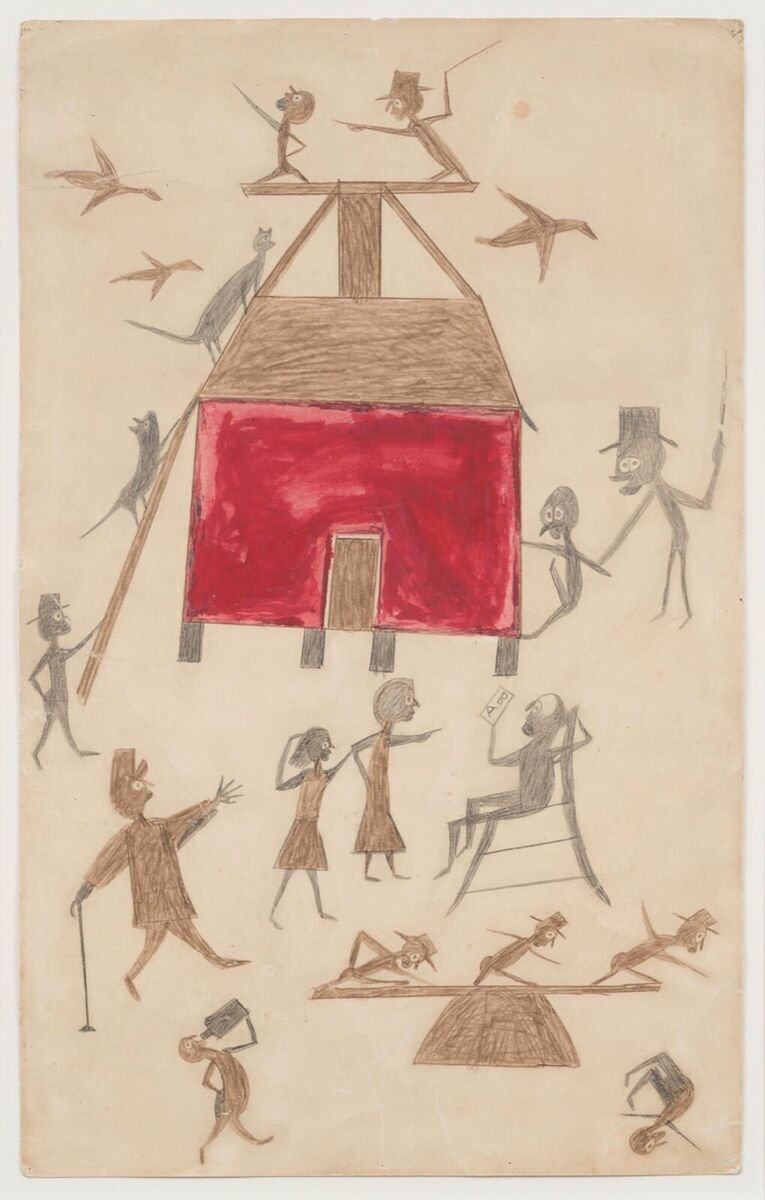

Red House with Figures

The red house is the central element, with a group of twelve men and two women. The women are in front of a man presumably teaching them, showing the passage of knowledge from men to women. In the introductory section of the Federal Writers Project, a collection of records and correspondence between editors and state directors within the program provides details about how the project was put together in 1937. These editor notes, instructions, and memorandums provide context for how the slave narratives were framed and curated. In a correspondence between Edwin Bjorkman, the North Carolina state director of the Federal Writers Project and George Cronyn, the Associate Director of the Federal Writers Project. George asked Edwin to include photos of the informants and to tell the photographers to make their subjects as simple as possible. He wanted the photographers to make the studies “simple, natural, and ‘unposed’ as possible”, further explaining that “ the background” should “be the normal setting” and, “the picture a visitor would expect to find by dropping in on one of these old timers” [6] The visual images included in the project were a reflection of the specific vision of the white writers and editors, not a representation that derived from the opinions of the informants. This key detail, sitting in opposition to Red House with Figures, shows the discrepancy between intentions between Traylor and Cronyn. Where Red House with Figures shows people in a state of constant movement, each figure acting with his or her own agency, the image of the slave cabin in Barbour County, near Eufaula, Alabama, shows a family posed in front of a slave cabin. In contrast to Traylor’s dynamism, this photograph is static, and the expressions of the subjects are emotionless and flat.[7] Comparing the two depictions of black women, the women in the photograph sat behind the men, donning aprons to denote their inescapable status as domestic workers. This is a stark contrast to the two outspoken women in Traylor’s work. Their lively expressions and strong stances point to the type of agency that would have been enviable to even the most self-empowered, educated white woman of this era. One woman is pointing at the man, as the woman behind her seems to follow suit. Compositionally, these women are the literal center of the painting and the center of all the action occurring in and around the red house. Despite not having many written words from Traylor, this drawing speaks volumes regarding his view of womanhood and the importance of women’s voices.

Untitled (Woman with Umbrella and Man on Crutch)

Man and Woman

Man and Woman with Dog

In Untitled (Woman with Umbrella and Man on Crutch), Man and Woman, and Man and Woman with Dog women are shown in relationships with men. It is unclear what their exact relationships are, however, what is clear is that the women are at least equal in size, they are on the same visual plane as their male counterparts, and they have strong stances. The first two are serious, while Man and Woman with Dog is much more playful with less of a focus on natural depiction. These paintings express a levity that is not otherwise seen in visual imagery in popular images of the the 1930’s, which is possibly a gatekeeping technique utilized by Traylor. According to Celeste Bernier, Traylor “safeguarded his visualizations of black psychological and physical complexity by rejecting the grotesque misrepresentations circulating in dominant White American visual and print cultures.”[8] These images are far from grotesque and are instead mundane and indicative of normal interactions one would experience with a partner. Delia Garlic, an informant from the Federal Writers Project, talked about her marriage to her husband in during the last days of slavery, and gives a blissful anecdote of their marital life where her husband made up a dance and performed it when her mood was low.

Untitled (Exciting Event/ Dancing woman)

Female Drinker

Leslie Umberger states that “mysterious people and frightening spirits populate the collected lore of the South and the Atlantic coast. The characters are not static in their natures. Regardless of which of them Traylor knew about, a high degree of flexibility or unfixed identity seems to have carried into his depictions of them.”[9] Women are not central to many of the folktales collected after slavery, and although Untitled (Exciting Event/ Dancing woman) and Female Drinker are not explicitly categorized as folktales by Traylor, these works have elements of the supernatural in both form and content. They deviate from the representational depictions of women aforementioned, with curvilinear shapes showing a more fluid range of motion. These works evoke mirror some of the tales mined and rewritten by the writer Virginia Hamilton, where black women and girls are the central figures in each story.[10] Traylor’s depiction of the female drinker and the dancing woman, show black women in contexts outside of motherhood, relationships, and all other domestic activities. They are free to exist in a world that blurs the lines between real and imagined worlds, which was a radical act in both white and black contexts. Folklore allows contemporary readers to understand aspects of life that were coded for the purpose of obscuration. Lawrence Levine, the author of Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom, was a Jewish- American historian who had previously written about histroy from the perspective of the leaders. His book was a way to solve the problem of getting past the written sources and to understand the history of people who did not leave behind written records. He says, “While I was reading and thinking about these issues, it occurred to me that African American folklore might prove an entryway into black thought during and after slavery”.[11] He cites the active oral culture, and centers his work around what happened to folk expression during and after American slavery. His conclusion is that slaves and their descendents shared information through lore, and that the way stories were repeated over time gives insight into the social dynamics during slavery, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow. Non-traditional research methods are used by Ingram in To Ask Again: Folklore, Mumbo Jumbo, and the Question of Ethnographic Metafictions. Ingram questions why the novel Mumbo Jumbo by Ishmael Reed is not considered a work worthy of critical analysis as a work of folklore and concludes that the work does not fit the criteria of “organic racial authenticity”.[12] She looks at the “new ethnography” of the 1970’s and 1980’s as a “project of translating the cultures of Others for a white, western audience”.[13]. In this way, literature and folklore cannot exist as a part of the self-narrated histories of marginalized people. In the opposite way, recorded history informs what folklorists’ study. Ingram says that “folklorists who study fiction, even while embracing the promises of "partial truths," still too often fall back on colonialist narratives that grant epistemological power to the West.” For these scholars to not accept Reed's “historiographic metafiction”[14] is a refusal to accept the agency that comes from black individuals writing their history through the lens of fiction. Ingram says “But the overarching theme of Mumbo Jumbo—in addition to its pointed commentary on issues ranging from the West's consistent and violent appropriation of African cultural forms to the failures of white liberalism— is that the West does not have complete epistemological control over history and the writing of culture, that alternative histories can and do exist”.[15]

The importance of Traylor’s depictions of women is expressed through his exaltation of black women in racialized, gendered, and fictional spaces. If they could exist freely in these three areas of life, there was the possibility for them to self-actualize and exist outside of the white, patriarchal gaze. We can witness the bridging of the visual and oral storytelling gaps in Going Urban: American Folk Art and the Great Migration, where Hartigan states, “Certainly discussions of Traylor's work have cited the concepts of memory and narrative, yet his role as a sidewalk storyteller is still underappreciated.[16] These memories and narratives give a glimpse into these visual primary sources that derived from Bill Traylor’s lived experiences in Alabama. In Between Worlds, the texts states, “Collectively, they relay the ways in which mystical ideas and oral culture take shape when put to paper.”[17] This is in reference to the tradition of many recorded black storytellers, who, like Traylor, used many ways to share both real and imagined stories. In Between Worlds, Leslie says that Traylor “was exploring realism, narration, symbolism, abstraction, as they intersected with the oral culture that inspired all his work”[18]. As Hartigan explained, “While a professional artist is likely to say, "My work is about ...," a storyteller often proceeds from the informal, less egocentric vantage: "There once was a man who...."[19] which is arguably the approach that Traylor took as an artist creating in the storytelling tradition. Looking through the lens of revisionist history, Traylor was ahead of his time, showing black women as multi-faceted, action-oriented, and opinionated.

Bibliography

Ausfeld, Margaret Lynne, Susan Mitchell Crawley, Leslie H. Paisley, Fred Barron, and Jeffrey Wolf. 2012. Bill Traylor: Drawings from the Collections of the High Museum of Art and the Montgomery Museum of FIne Arts. Atlanta: Prestel Publishing.

Bernier, Celeste-Marie. 2013. "Unseeing the Unspeakable: Visualizing Artistry, Authority and the Anti-Slave Narrative in Bill Traylor’s Drawings (1939-1942)." Slavery & Abolition Vol. 34 (2): 266-280.

Dorson, Richard M. 1975. "African and Afro-American Folklore: A Reply to Bascom and Other Misguided Critics." The Journal of American Folklore Vol. 88 (348): 151-164. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/539194.

Hamilton, Virginia. 1995. Her Stories: African American Folktales, Fairytales and True Tales. New York: Blue Sky Press.

Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe. 2000. "Going Urban: American Folk Art and the Great Migration." American Art Vol.14 (2): 26-51.

Ingram, Shelley. 2012. "To Ask Again’: Folklore, ‘Mumbo Jumbo’, and the Question of Ethnographic Metafictions." African American Review Vol. 45 (1/2): 183-196. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23783445.

Levine, Lawrence W. 2007. Black Culture and Black Consciousness : Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom. Cary: Oxford University Press.

Moody-Turner, Shirley. 2021. "Tracing a Black Folklore Practice: Frank D. Banks and the Journal of American Folklore." Journal of American Folklore Vol. 134 (533): 346. https://link-gale-com.ezproxy.lib.utexas.edu/apps/doc/A675525429/LitRC?u=txshracd2598&sid=summon&xid=242a9637.

1934. "Negro Woman Granted Clemency." The Tuscaloosa News. February 6.

Patrick B. Mullen, Aaron N. Oforlea. 2012. "Introduction: Critical Race Theory and African American Folklore." The Western journal of black studies Vol. 36 (4): 251-252. link.gale.com/apps/doc/A314347780/PPDS?u=txshracd2598&sid=bookmark-PPDS&xid=2a889d8f.

1941. Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the Uniited States From Intervies with Former Slaves. Type-Written Records Prepared by the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938, Assembled by the Library of Congress Project, Work Projects Administration. Washington.

Umberger, Leslie, and Kerry James Marshall. 2018. Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor. Washington D.C.: Princeton University Press.

[1] Umberger, Leslie, and Kerry James Marshall. 2018. Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor. Washington D.C.: (Princeton University Press), 32.

[2] Umberger, Between Worlds, 79.

[3] Umberger, Between Worlds, 67.

[4] 1941. Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves. Type-Written Records Prepared by the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938, Assembled by the Library of Congress Project, Work Projects Administration. Washington. 129.

[5] “Negro Woman Granted Clemency” The Tuscaloosa News, February 6, 1934.

[6] 1941. Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves. Type-Written Records Prepared by the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1938, Assembled by the Library of Congress Project, Work Projects Administration. Washington, xvi.

[7] Slave Narratives, 2.

[8] Bernier, Celeste-Marie. 2013. "Unseeing the Unspeakable: Visualizing Artistry, Authority and the Anti-Slave Narrative in Bill Traylor’s Drawings (1939-1942)." Slavery & Abolition Vol. 34 (2): 272.

[9] Umberger, Between Worlds, 89.

[10] Hamilton, Virginia. 1995. Her Stories: African American Folktales, Fairytales and True Tales. New York: Blue Sky Press.

[11] Levine, Lawrence W. 2007. Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom. Cary: Oxford University Press.

[12] Ingram, Shelley. 2012. "To Ask Again’: Folklore, ‘Mumbo Jumbo’, and the Question of Ethnographic Metafictions." African American Review Vol. 45 (1/2): 183-196. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23783445.

[13] Ingram. To Ask Again, 190.

[14] Ingram. To Ask Again, 192.

[15] Ingram. To Ask Again, 196

[16] Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe. 2000. "Going Urban: American Folk Art and the Great Migration." American Art Vol.14 (2): 32.

[17] Umberger, Between Worlds, 105.

[18] Umberger, Between Worlds, 136.

[19] Hartigan, Going Urban, 50.